Scientific Program

Keynote Session:

Oral Session 1:

- Place of Citicholine and Neuroregulators in prevention, reduction of sequelae neurological and morbidity and mortality.

Title: Place of Citicholine and Neuroregulators in prevention, reduction of sequelae neurological and morbidity and mortality.

Biography:

Dr. Lamirez Diasivi Nzuzi is working for the department of neurosurgery at Mont-Amba University Hospital Center (CHMA), University of Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo

Abstract:

NEWS ON NEUROPALARIA: BROCA's aphasia complicating encephalitis acute malaria, Approach Neuroadapted Therapeutics: Place of Citicholine and Neuroregulators in prevention, reduction of sequelae neurological and morbidity and mortality.

Clinical cases, CHMA / UNIKIN, March 2021

Context:

Cerebral malaria, acute malarial encephalitis due to Plasmodium falciparum: is an acute brain injury whose outcome may be fatal can lead to polymorphic neurological sequelae: hemiplegia / hemiparesis, speech disorders (motor aphasia de Broca, Sensory aphasia of Wernicke), behavioral disturbances, cognitive impairment, blindness, secondary epilepsy. In Africa Sub-Saharan, and more particularly in the DRC, Neuropalaria, knows a high frequency of neurological lesions with a very high lethality and the seriousness of their repercussions on the fate of the children who are victims of it. The neuropathological severity of acute malarial cerebral aggression is correlated with the high parasite density, with the phenomena of sequestration and cytoadherence, the inflammatory process, the presence of the factors of bad prognosis or ACSOS, the diagnostic and therapeutic delay; and the antimalarials, do not modify the evolutionary process of neurological lesions and those of sequelae. An approach Neuroadapted therapy (Citicholine and neuroregulators) introduced in our patients, from the acute phase (from D0: in first 24 hours / first 6 hours +++ to 7 days), until the stabilization phase (D0- 30 days), allowed us to: Improve perfusion of the areas of ischemic brain suffering, regulation of cerebral metabolism (aerobic glycolysis +++) and reduction of cerebral edema (vasogenic, cytotoxic +++); delay the evolution of the destruction of the neuronal membrane and neuronal degeneration; limit and block ischemic cascades leading to neuronal necrosis; Improve the prognosis and dramatic rapid recovery, speech recovery and significant reduction in other neurological sequelae, but also death-mortality.

To date, acute malarial encephalitis should be considered in mind as a normotensive ischemic stroke. post-infectious, until proven guilty, in the light of the neuroanatomo-clinical correlation, of the neurophysio- pathologies induced in acute and secondary cerebral aggression.

Goal:

Management of acute malarial encephalitis and its acute complications, and to propose a Neuroadapted therapeutic approach, by demonstrating the action of Citicholine and neuroregulators on Broca's area.

Methodology:

A serial study of cases admitted to the Emergency and Neuropediatrics Department for acute malarial encephalitis complicated by aphasia de Broca and other neurological sequelae.

Results

In the absence of certain medical files available and in the insufficiency of clinical and para-clinical data found in certain records, of the 30 patients registered for acute malarial encephalitis complicated by neurological deficits during the period of March 2021, we describe that two cases of Broca's Aphasia on Acute Malarial Encephalitis in two patients born and residing in DRC, Kinshasa. The first case; a 9-year-old male child admitted to the neuropediatric emergency room for tonic-clonic seizures and headaches, in his antecedents, no notion of previous seizure episode, no convulsors and epileptics in the family. Treatment received elsewhere, Quinine, Ciprofloxacin and Diazepam; In whom we note mainly at physical examination, Heart rate at 140 bpm, Respiratory rate at 40 cpm, Temperature at 38 ° C, Coma with convulsions

Tonic-clinical, febrile on palpation, colored eyelid conjunctivae and anicteric bulbar conjunctiva, an abdomen not bloated, sensitive to medium ureteral points and without organomegaly, Deep coma, Soft neck and no signs of neuro-irritations meningeal, isocoric and reflective pupils. On paraclinical examination, Hb at 12 g / l, occasional glycemia at 109 mg / dl, GE: Tropho +++, GB: 16000 elt and FL: N60% L40%; Widal (TH: 1/160, TO: 1/160), Blood ionogram, CT-brain scan and emergency EEG not performed, a treatment was initiated: made of injectable Artesunate (H0-H72), Oritaxim, Amikacin, Ciprofloxacin, a maintenance infusion :( SG5% + electrolytes + Nootropyl + Azantac) and feeding by gavage. The evolution would be marked on D5-D7 by an awakening initiated with Brocas motor aphasia, right hemiparesis, CT scan of the brain, performed: Left frontal hypodensity zone. Under Citicholine(Somazina) and Neuroregulators (Gamalate B6, Surmenalite), resumption of language 24 hours later, with end of tremors (impairment of central gray nuclei) under Artane ½ tablet for 7 days with a good spectacular development. File close and exit authorized with Trausan, Surmenalite and Gamalate B6 for 1 month; an appointment in 1 month with a cerebral CT-scan control.

The second case; she is a 27-year-old patient, admitted for temporo-spatial disorientation and headache. contributory, in whom the clinical examination notes a BP: 158/87 mm Hg, HR: 112bpm, FR: 24 cpm, patient with temporal disorientation spatial, EG altered by suffering mine, Colored eyelid conjunctiva and bulbar anicteric, on normal gynecological examination, on neurological examination; flexible neck and no signs of neuro-meningeal irritation, isocoric and reflective pupils. At the exam paraclinical; GE: Tropho +; incidental blood sugar: 112 mg / dl, Hb: 12 g / l, ESR: 60mm / H, GB: 12200elt, FLN62% L38%, Urinary sed (GB: 5-10 / elt, EC: 5-10 / elt), treatment with Artesunate, promethazine, ceftrin plus. The evolution was marked by a motor aphasia of Broca, a few hours after admission, a cerebral CT scan was urgently requested, not carried out given the financial situation patient, and she was on citicholine (Somazina) as a continuous infusion with antioxidants (VIT C, VIT E) in emergency, neurosedation with phenobarbital. On day 1 of hospitalization, i.e. 24 hours of hospitalization later, we observed the resumption of speech with temporo-spatial orientation, and vital signs in physiological norms. File close and exit authorized with Somazina tablet, Gamalate B6, Overmenalitis for 1 month.

Conclusion:

Before any case of acute malarial encephalitis (cerebral malaria), it is of interest to add the neuroregulatory therapeutic regimen; improving the prognosis (rapid recovery), preventing the occurrence of neurological complications often irreversible and reduced morbidity and mortality. And Antimalarials, do not modify the evolutionary process of destruction neuronal and neurological sequelae.

Dr. Lamirez DIASIVI NZUZI

E-mail: lamirezdiasivi1@gmail.com

Phone: +243892383193

Mont-Amba University Hospital Center (CHMA) / University of Kinshasa

REFERENCES

1. Stephane Jaureguiberry: Elements of the pathophysiology of severe P. falciparum malaria. Center for Immunology and Diseases infectious diseases of Paris, University of Pierre Marie Curie (Sorbonne University). 2018

2. The e-PILLY TROP, book on tropical infectious diseases. Web edition 2012

3. Mr Abdramane Ombotimbé: Thesis: Study of the sequelae of cerebral malaria in the pediatric department of the Hospital Center. academic Gabriel Toure from January 2009 to February 2010.

4. Evelyne AVOUNE N .: Thesis: Management of neuropediatric emergencies. Sidi Mohamed University, Ben Abdellah, Morocco. 2018.

5. Practical Guide: Managing Severe Malaria, WHO. 2019

6. Neuropharmacology book, University of Pierre Marie Curie (University of Sorbonne).

7. Neurology Med line book, Acute Malarial Encephalitis.

8. Prof SITUAKIBANZA, Course in infectious pathology. Kongo University.

9. Lamirez DIASIVI: Elements of Adapted Neuroanatomy. Cranio-encephalic component, Volume I.

10. Aude Coutier, Olivier Calvetti, Article: Citicholine and neuroprotection, “a promising molecule”. Service of Prof JA Sahel, Center Hospitalier National de Quinze –Vingt, Paris. 2020

11. BURNOL Laetitia, IDE Angélique Faveyrial: Secondary cerebral attacks of systemic origin (ACSOS). CHU Saint Etienne. Lyon 2017

12. Infectious and vascular neuropathology, University of Pierre Marie Curie (Sorbonne University).

13. Jean-François Payen: Cerebral edema: from pathophysiology to clinical practice. Department of Anesthesia-ResuscitationGrenoble.

14. Philippe Meyer, Eleonora Terzi, Julie Streit: Management of HTIC in children. Neuro-anesthesia - Resuscitation. Paris UniversityDescartes. 2017

15. Infectious neuroimaging, Med-lin.

Oral Session 2:

- Intraventricular aneurysm of the distal segment of the anterior choroidal artery: A case report and review of literature.

Title: Intraventricular aneurysm of the distal segment of the anterior choroidal artery: A case report and review of literature.

Biography:

Karrar Aljiboori is a senior medical student at Michigan State University College of Human Medicine. His goal is to contribute to the advancement of the neurosurgical field. His interests include creation of surgical instruments, cerebrovascular neurosurgery, and general neurosurgery.

Abstract:

ABSTRACT:

Anterior choroidal artery (AChA) aneurysms at the junction of the ICA and AChA are the most common AChA pathology, and they account for approximately 2-5% of all intracranial aneurysms; however, aneurysms of the distal segment of the (AChA) are extremely rare. We report a case of a 73-year-old male who presented with altered mental status. Non-contrast computed tomography (CT) of the head showed extensive intraventricular hemorrhage that is most intense in the right temporal horn. Initial computed tomography angiography (CTA) revealed a lobulated enhancing structure with a vascular pedicle in the right temporal horn. Digital substruction angiography (DSA) confirmed the presence of a ruptured aneurysm in the intraventricular segment of the AChA. The aneurysm was not amenable to endovascular treatment due to a stenotic proximal AChA. The patient underwent a right transtemporal transventricular approach and clip placement. To our knowledge, our report introduces the use of BrainPath for the first time for aneurysmal clipping involving the intraventricular AChA. This case emphasizes the consideration of intraventricular AChA aneurysms as a possible cause of intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH). We also review the current literature on AChA.

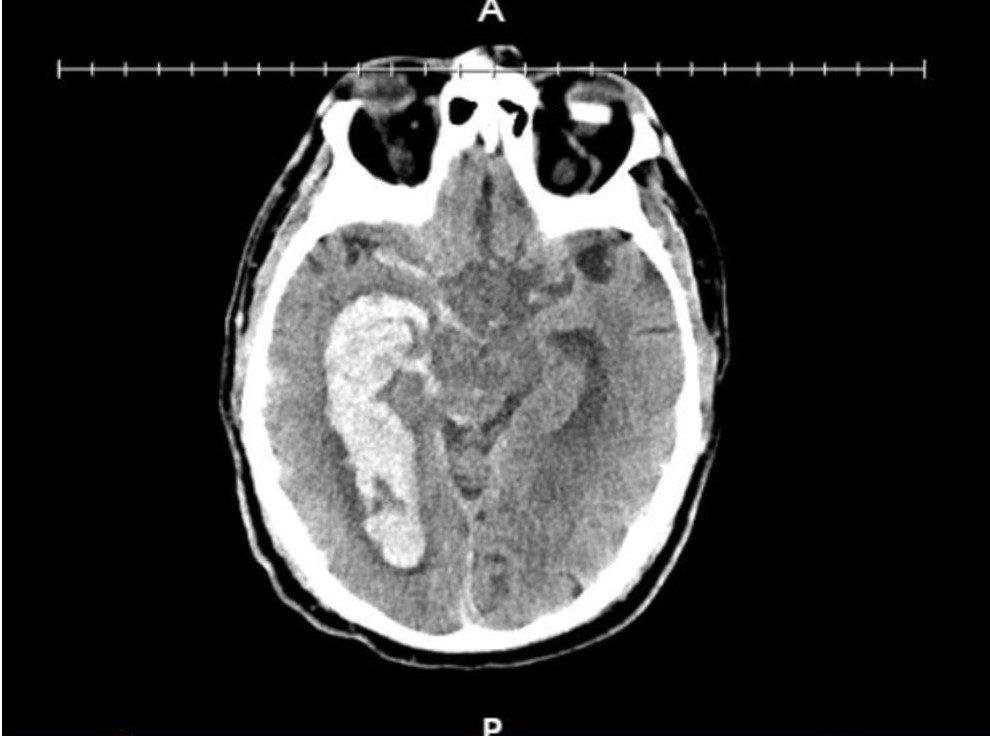

Figure 1: Initial head CT without contrast

Extensive intraventricular hemorrhage in the right and left lateral ventricles as well as the third and fourth ventricles (not shown in image). Extension of hemorrhage into the right sylvian cistern, basal cistern.

References

1. Ghali, Michael George Zaki et al. “Anterior Choroidal Artery Aneurysms: Influence of Regional Microsurgical Anatomy on Safety of Endovascular Treatment.” Journal of cerebrovascular and endovascular neurosurgery vol. 20,1 (2018): 47-52. doi:10.7461/jcen.2018.20.1.47

2. Yu, Jing et al. “Clinical importance of the anterior choroidal artery: a review of the literature.” International journal of medical sciences vol. 15,4 368-375. 12 Feb. 2018, doi:10.7150/ijms.22631

3. Zhang, Nai et al. “Using a New Landmark of the Most External Point in the Embolization of Distal Anterior Choroidal Aneurysms: A Report of Two Cases.” Frontiers in neurology vol. 11 693. 31 Jul. 2020, doi:10.3389/fneur.2020.00693

4. Rutledge, Caleb et al. “Transcortical transventricular transchoroidal-fissure approach to distal fusiform hyperplastic anterior choroidal artery aneurysms.” British journal of neurosurgery, 1-5. 22 Apr. 2019, doi:10.1080/02688697.2019.1594691

5. Feijoo, Pablo García et al. “Management of a ruptured intraventricular aneurysm arising from distal anterior choroidal artery (AChA): pediatric case report.” Child's nervous system : ChNS : official journal of the International Society for Pediatric Neurosurgery vol. 37,5 (2021): 1791-1796. doi:10.1007/s00381-020-04888-w